From the wings to the spotlight

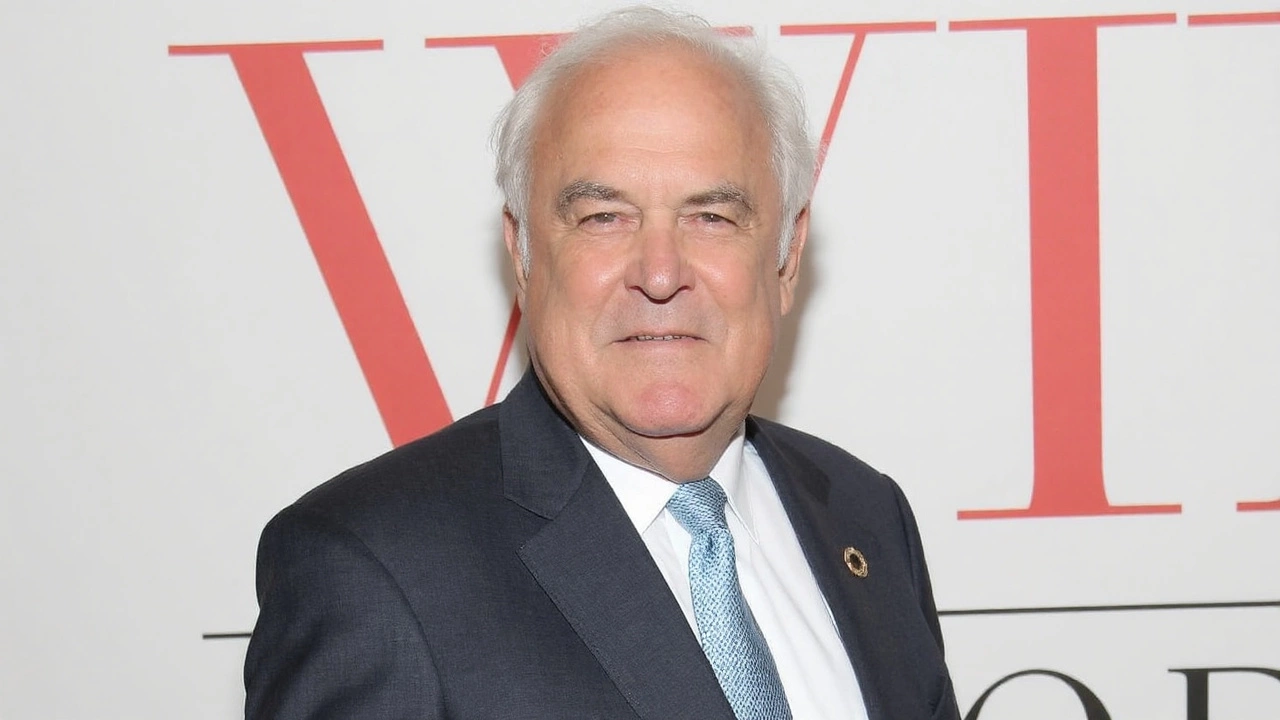

He was ready to retire. In the early 1990s, after decades calling cues and solving crises for other stars, Jerry Adler figured his time in show business had peaked. He joked to a reporter that he was heading into “the twilight of a mediocre career.” Then a casting director took a chance, a director felt a jolt in the audition room, and everything that came before—Yiddish theater lineage, Broadway’s golden age, and years of behind-the-scenes grind—suddenly added up to a second act most actors only dream about.

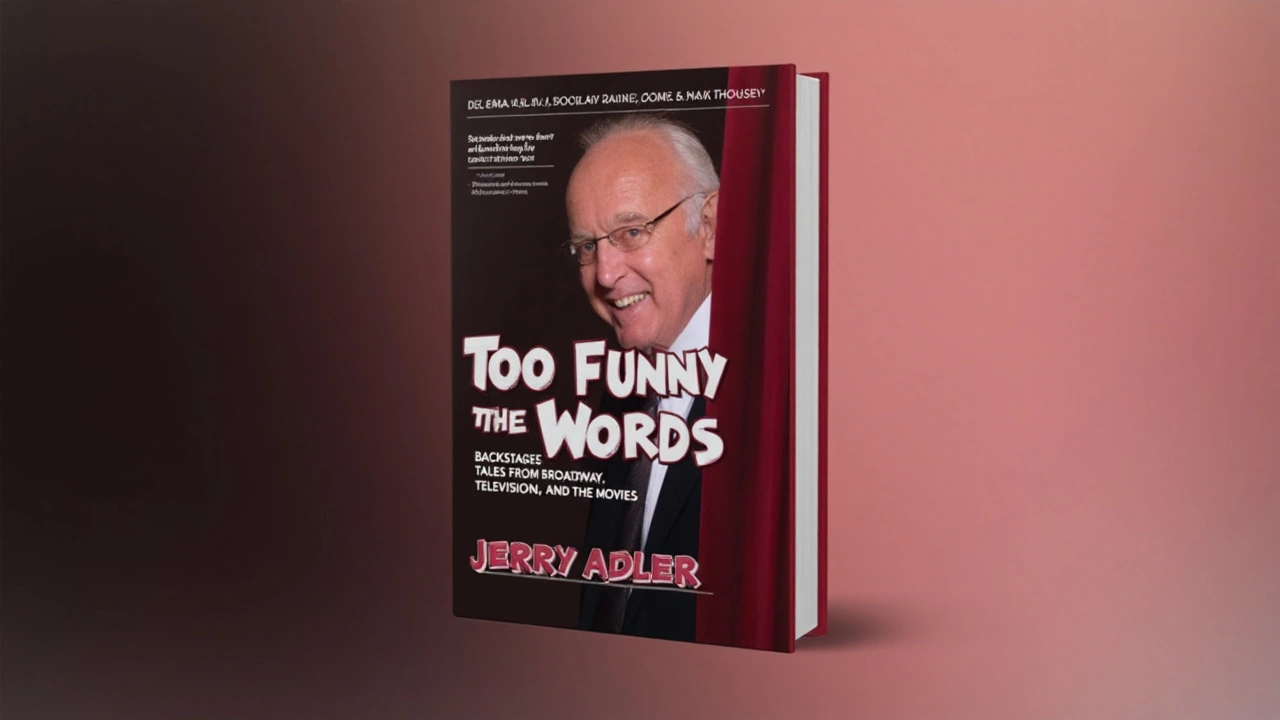

Adler’s new memoir, “Too Funny for Words: Backstage Tales from Broadway, Television and the Movies,” released in 2024, is the long, winding story of how a kid from Brooklyn born on February 4, 1929, spent decades in the shadows of the stage only to become a familiar face on one of television’s defining dramas. The surprise isn’t that he has stories; it’s how many rooms he was in before any of us knew his name.

His show-business roots run deep. The Adler name is theater royalty. His great-uncle Jacob Pavlovich Adler was a giant of the Yiddish stage. Cousins Stella and Luther Adler shaped American acting for generations. His father, Philip, managed Broadway and touring productions for decades and served as general manager of the Group Theatre—the 1930s collective that helped push American drama toward realism and seeded the methods that reshaped acting classes for years to come.

Adler didn’t start with the spotlight. He started with a headset. In 1956, during the out-of-town tryout of My Fair Lady at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven, he served as stage manager on a production that would become one of the most famous musicals of its era. He was in the room with Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews as the show found its rhythm. This was the kind of backstage job that requires everything: keeping the crew tight, soothing nerves, juggling changes, and calling the show so the audience never felt the chaos humming behind the curtain.

Stage managers are air traffic controllers with a script. If a costume tears, a prop breaks, or a star misses a cue, they are the fixers. Adler thrived there. Over the years he worked close to some of the biggest names in show business—Marlene Dietrich, Julie Andrews again, Richard Burton—and learned the unglamorous truth that carries every production: the quiet professionals save the day, and nobody outside the room ever knows.

By the 1980s, Broadway hit a slump. Rising costs, changing tastes, and lean box office made steady jobs harder to find. Adler headed west to California, looking for work in television, landing on the production side of shows like the daytime soap Santa Barbara. It wasn’t starry, but it was steady. Then came the pivot he never saw coming.

In 1992, casting director Donna Isaacson—connected to Adler’s family through one of his daughters—pushed for him to audition for The Public Eye, a period drama starring Joe Pesci and written and directed by Howard Franklin. Adler read for a newspaperman. Franklin reportedly felt chills in the room. The take wasn’t showy. It didn’t need to be. It was grounded, lived-in, and real—the kind of performance that signals a performer who has already spent a lifetime studying people up close.

That job opened the door, and he started showing up more often on camera. An early TV turn on Northern Exposure led to more work. Casting teams took that first impression and ran with it. He was no longer the invisible hand on the headset. He was in the scene.

From Hesh to Howard Lyman: a late-career run on TV and film

The role that made him recognizable to millions came from David Chase, whose later project would change television outright. On The Sopranos, Adler played Herman “Hesh” Rabkin, an old friend of Tony Soprano and a man with deep history in New Jersey’s music business and the Soprano family. Hesh wasn’t loud muscle. He was counsel—Tony’s sounding board—often the one in the room who understood how money really moved and when pride got in the way. Adler’s restraint gave the character weight. He didn’t need to steal a scene to own it; the silences did work for him.

Adler’s camera career spanned more than three decades once it started. He turned up in films like Manhattan Murder Mystery, In Her Shoes, and Prime, bringing the same calm, sly energy to each. On television he became a steady presence: the building’s deadpan maintenance man Mr. Wicker on Mad About You; a recurring turn as Howard Lyman on The Good Wife and its spinoff The Good Fight; a patriarch opposite Bob Saget on Raising Dad; Fire Chief Sidney Feinberg on Rescue Me; and memorable appearances on Transparent, Broad City, and Living with Yourself. You didn’t always expect him in a scene, but when he showed up, the center of gravity shifted a little.

The memoir doesn’t just collect credits. It collects the mess, the close calls, and the near-misses that never make the press notes. There’s a story about a brush with President John F. Kennedy that almost went sideways, the kind of backstage comedy that only feels funny decades later. There are pages on working with Katharine Hepburn, where the lesson isn’t just about how to act but how to behave in a room where everyone is watching the pro at the center. Adler writes like someone who has run shows and lived in the margins: quick with details, honest about the unglamorous parts, and appreciative of the people who kept the trains on time.

Part of the draw here is perspective. Most showbiz memoirs come from stars who lived at the top of the call sheet. Adler spent most of his life watching the top from five feet away, organizing the chaos they left behind, then—much later—stepping into the light himself. He knows who actually holds a production together. He’s been the one hunting for a missing prop while a scene partner stalls. He’s been the guy reminding a director that the scene change won’t fit in the time they think it will. And he’s been the actor who hears his first name in a grocery store and wonders, for a second, how the world learned it.

He has said he once thought he was too goofy-looking to be an actor. After years in the booth and in rehearsal halls, being recognized in public felt odd. Watching himself on screen felt even stranger. But the late start also gave him freedom. He wasn’t chasing stardom. He was doing the work—show up, hit your mark, say the line, and serve the scene. Directors like that. So do ensembles.

The Sopranos changed more than his visibility. It reset what television could do. The show made room for quiet performances and morally complicated characters. Hesh fit that world: not a villain, not a saint, a man with history and leverage who understood that advice can be as dangerous as a threat. Adler’s scenes with Tony often played like a counterweight—a reminder that power has a long memory.

When he moved into The Good Wife and The Good Fight, he carried that same touch. Howard Lyman wasn’t Hesh—different world, different stakes—but the sense that this man had been around long enough to know better landed the same way. On Rescue Me, he brought authority without bluster. On Transparent and Broad City, he folded into shows with their own sharp tones and found angles that worked. If you remember him as Mr. Wicker on Mad About You, you remember the dry humor. If you remember him from Manhattan Murder Mystery, you remember the easy give-and-take that keeps a scene alive.

The book’s title, “Too Funny for Words,” nods to a life where the best lines rarely happen on stage. They happen in rehearsal when someone forgets page three. They happen in a dressing room at half-hour call. They happen when a superstar solves a problem in five seconds flat, and everyone else realizes they’ve been overthinking it. Adler has those in bulk because he paid attention in the years nobody else was looking his way.

The family history matters here. Coming from the Adlers gave him a front-row seat to a tradition where theater wasn’t just a job; it was a language. The Yiddish stage taught audiences to expect emotional truth. The Group Theatre pushed that truth into mainstream American drama. You feel those currents in how Adler writes about rehearsal, about the respect due to craft, and about how a room full of egos still needs a plan.

He also writes about the leaner times with humor. The 1980s were tough on Broadway. Budgets tightened, hits were rarer, and every new project felt like a gamble. Heading to Los Angeles wasn’t glamorous; it was practical. Santa Barbara wasn’t the kind of gig he would brag about, but it kept him in the game. Then the audition that changed everything proved a lesson many actors know and few can plan for: the right role lands when you’re already prepared to do it.

Why does a backstage veteran make such a good on-camera actor later in life? Because he understands timing, listens hard, and respects the crew. He knows that a performance isn’t just a close-up; it’s a camera setup, a sound check, and a prop handoff timed to the syllable. He knows how to adjust without complaint when the day runs long. Sets run on that energy. Directors hire it again.

Adler’s memoir also taps into a cultural record that can fade fast. The out-of-town tryout circuit—New Haven, Boston, Philadelphia—was once a lifeline for Broadway. Shows found their shape there. Stage managers like Adler kept the wheels on while writers ripped apart scenes overnight and designers rebuilt sets before lunch. The book captures that texture: the smell of paint in the wings, the typed notes in the margins, the panic that turns into a fix right before places are called.

Readers looking for gossip will get brushes with legends, but the better payoff is the working knowledge. How does a near-disaster with a sitting president get cleaned up before it hits the papers? What do you learn from an afternoon with Hepburn that changes the way you walk into a room forever? Adler keeps the focus tight: here’s what happened, here’s what it meant on the job, here’s the part I couldn’t see until years later.

He’s 95 now, and the long view helps. Careers aren’t straight lines. They’re chapters that look random until someone lays them next to each other. The young stage manager who kept My Fair Lady on time, the middle-aged fixer who made television schedules work, and the late-blooming actor who steadied Tony Soprano—they’re the same person moving through the same business, learning how to be useful in different ways.

If you came to him through The Sopranos, the memoir will send you backward, into rehearsal halls and loading docks where Broadway legends still had to hit their cues. If you first knew him as Mr. Wicker, you’ll see how that dry delivery came from years of watching people under pressure. And if you’re coming to the story cold, the appeal is simple: here’s an insider’s view of how the entertainment machine really runs, told by someone who has done almost every job but sell the tickets at the door.

There’s also a gentle note about fame. Adler admits public recognition felt odd after so long behind the scenes. Seeing himself on screen was stranger. But the fame that arrived wasn’t the kind that turns a life upside down. It was the kind that buys you another call, another chance to do good work, another day on a set where a dozen people quietly make you look better than you are. He never forgot to credit them.

For readers who love the craft as much as the lore, this book reads like a guided tour. You get the rehearsal room politics without the score-settling, the actor’s tricks without the self-help tone, and just enough near-catastrophe to remember that theater and television are live enterprises even when they’re recorded. What seems effortless on stage or on screen is almost always the product of nerves, negotiation, and a stage manager who still has a pencil behind his ear.

Adler’s story lands differently because it respects every rung of the ladder. It doesn’t pretend the breaks weren’t lucky. It doesn’t downplay the grind. It just keeps moving forward, scene by scene, until a lifetime spent offstage becomes the perfect training ground for a late, steady run on camera.

Key moments in a seven-decade career:

- 1929: Born in Brooklyn into the Adler theater family, with ties to Jacob P. Adler and cousins Stella and Luther Adler; father Philip works across Broadway and the Group Theatre.

- 1956: Stage manager during the out-of-town tryout of My Fair Lady at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven as the musical finds its shape with Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison.

- 1960s–1970s: Builds a reputation in theater direction and production, working with marquee names and handling the day-to-day crises audiences never see.

- 1980s: Broadway cools; he shifts to television work in California, including the soap Santa Barbara.

- 1992: Lands The Public Eye after a pivotal audition for director Howard Franklin, moving firmly into on-camera roles.

- 1990s: Appears on Northern Exposure and in films such as Manhattan Murder Mystery, carving out a niche as a grounded character actor.

- 1999–2007: Becomes a recurring presence on The Sopranos as Herman “Hesh” Rabkin, Tony Soprano’s longtime friend and advisor.

- 2000s–2010s: Recurs on The Good Wife and The Good Fight as Howard Lyman; plays Mr. Wicker on Mad About You; turns up in Rescue Me, Transparent, Broad City, and Living with Yourself; appears in films like In Her Shoes and Prime.

- 2024: Publishes “Too Funny for Words,” collecting decades of backstage and on-set stories with clear-eyed humor.

The memoir’s charm is simple: it puts you in the rooms where careers are made—rehearsal halls, cramped TV stages, location shoots before dawn—and lets you watch the work. Adler may have come to fame late, but he arrives with a lifetime of detail. That’s the book’s real reward: the feeling that you’ve been standing just offstage, headset on, hearing the whole show click into place.